The New York-based Esperanto publisher Mondial has published its 100th book of original fiction (prose and poetry)—a milestone! Half of these books are part of the "Beletra Almanako" series (published in book format), each volume of which is filled with original prose and poetry. The other half are novels, short stories, and poetry collections in Esperanto. In addition, there are a number of original Esperanto textbooks and dictionaries by Esperanto authors.

Notes about Esperanto Literature: original and translated, fiction and non-fiction

Since the world outside of the Esperanto movement has, in general, no idea that there is a rich literature in Esperanto and that there are flourishing publishing houses, book distribution centers (local and online), and, of course, avid readers in most countries of the world, we will present here some of our titles to the English speaking world. Since the beginnings of Esperanto, almost 140 years ago, books have been written in this international language. With each decade, with more and more authors from all continents, Esperanto literature has become a mature and nuanced literature with stylistic diversity, and covering all kinds of genres. Original novels, short stories, poetry, and specialized books are published every year. This website wants to present – in English – some of the titles, in the hope that the widespread ignorance of the literature in the international language Esperanto will be, one day, a thing of the past. Please come back soon to see new books.

The Esperanto publisher Mondial publishes books in and about Esperanto, works originally written in Esperanto and books translated from many languages into Esperanto. It publishes fiction and non-fiction: prose, poetry, dictionaries, and specialized books dealing with various topics.

TO SEE ALL OF OUR BOOKS IN AND ABOUT ESPERANTO: www.esperantoliteraturo.com

List of links to Esperanto books presented on this site

Click the links to read more about the books in the international language Esperanto:

- Sten Johansson: "Falaflo en maco" ("Falafel in a matzoh" - novel written in Esperanto)

- Argus (Friedrich Ellersiek): "Pro kio?" ("What for?" - novel written in Esperanto)

- Sten Johansson: "Sesdek ok" ("Sixty-eight" - novel written in Esperanto)

- Trevor Steele: "Sed nur fragmento" ("But only a fragment" - novel written in Esperanto)

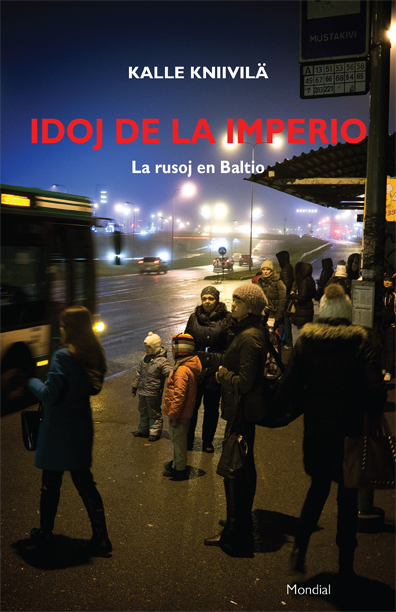

- Kalle Kniivilä: "Idoj de la imperio. La rusoj en Baltio" ("Children of the Empire. The Russians in the Baltic States" - specialized book written in Esperanto: politics; journalism)

- George Orwell: "Mil naŭcent okdek kvar" ("Nineteen Eighty-Four"; "1984"; novel; translation into Esperanto, from English)

Sten Johansson: "Falaflo en maco (Falafel in a matzoh)"

This is a novel (2023) written originally in Esperanto (i.e. not translated from any other language) by the Swedish Esperanto author Sten Johansson. Born in 1950 and one of the best-known modern writers of fiction in Esperanto, Johansson has written more than 25 books in the international language Esperanto, mostly novels and short stories. He also translates into Esperanto and writes in Swedish, his native language.

ISBN 9781595694461

156 pages

Order in Europe: UEA (Rotterdam)

Order in North America: Mondial (New York City)

ABOUT THE BOOK: Filippa, a young Swedish woman – a gardener – from the southern Swedish city of Malmö, not only finds her own life somewhat monotonous, but also sees herself between two worlds: On the one hand, her boyfriend, Kasim, who was born in Sweden, had grandparents who – due to Israeli military operations in Gaza – had to flee Palestine to Lebanon, and has a father who was born in the Beirut refugee camp but later moved to Sweden because of the war in Lebanon…

Here is a rough English translation of the beginning of a chapter of the novel:

A cardboard card hangs from a string around his neck. It says his name, Wilhelm Halder, and the day he was born, November 5, 1934. That's what the lady who tied it to him said. The lady in the gray dress with a red cross on her chest.

A month ago he celebrated his fourth birthday with Mother and Grandmother, but now Mother has given him to this gray lady who speaks in a slightly strange way. Mother explained that the lady would take him to Aunt Willi and some ladies and gentlemen whose names he doesn't remember. Why couldn't he stay with Mother and Grandmother in the home in Vienna, where he's always lived? Mother did explain why he had to travel, but he can't remember that either. Did she say when she would come to pick him up herself? Tomorrow or a little later? On Hanukkah? Or in the summer? He doesn't know anymore.

He does know, however, that Mother and Grandmother are sad because Grandfather is dead. It happened in the spring, which was a long time ago. He is not sure if he remembers Grandfather or only the stories about him. Grandfather's violin remained on the wall, but some time ago Mother took it away because they needed food. He does not know where that death is, where Grandfather went. Is it with Aunt Willi? Mother often spoke of that aunt, but now he cannot remember what she said. Maybe he will meet Grandfather again, but he does not know how to recognize him if that really happens.

The violin was for making music, but Wilhelm was not allowed to touch it. Only Grandfather could play it. But after he died, he could not play either. So Mother did well when she exchanged it for food. Food is more important than music when you are hungry. But Grandmother did not agree. She wanted to keep Grandfather's violin. Grandmother does not eat very much.

The gray lady does not have time to worry much about him, because she has a whole bunch of other children. Some are older, some are younger, but each of them wears a cardboard slip around their neck. They are all put into a small room in a carriage, which the lady calls a compartment. The carriage soon starts rolling, and then he notices that Mother is no longer with him. They sit very close together on the seats and floor, and the lady is standing, carrying a small child on her arm. One boy has wet his pants, and now he is sitting on a newspaper, while the pants are hanging from a shelf. The lady gives everyone a cookie. Wilhelm and most of the others eat it immediately and then look at a girl who is keeping hers in her hand. One boy tries to snatch it from her, but he only gets a slap from the gray lady, and the whole place is filled with crying. The slapped boy cries, the little child on the lady's arm, the girl with the cookie and two siblings on the other bench. Then Wilhelm also cries a little, when no one notices. He had not dared before. From outside he smells the smell of coal smoke, which he recognizes from the home fireplace. The gray lady carefully closes the window so that the smoke does not come inside. The carriage rolls along for a long time, while it sometimes shakes, and from outside there is a clicking sound: boom-boom, boom-boom, boom-boom, and sometimes a loud howl. This is the locomotive, says the lady. Outside the window, hills pass by with forests, fields, water, houses, chimneys, churches, masts and more hills. Sometimes they stop, and people get out or go into other carriages or rooms, but not here, where the children are sitting. Wilhelm gets tired, doeszes off, wakes up from some kind of shock, falls asleep again while sitting, and wakes up again when someone pushes him.

The journey continues endlessly. He hardly hears the horns anymore, nor does he feel the jolts of the carriage. It becomes evening and night, and morning again. The children are still sitting or half-lying on top of each other, now sleeping, now looking around, now arguing or crying. The lady has laid the sleeping baby on a shelf above the sitting ones and rearranged the children so that she herself can get a small seat. In the morning, when the carriage is standing still somewhere, she gets out. Before leaving, she tasks the eldest girl with looking after the little ones. Wilhelm thinks that now he has lost the lady too, but after a while she returns with a bag of bread rolls and two bottles of milk, which she gives to one child after another. Only then does he realize that he is very hungry....

Argus (Friedrich Ellersiek): "Pro kio?"

This is the first crime novel written originally in Esperanto and published first in 1920. The Esperanto style and vocabulary of our 2008 edition has been slightly modernized by the editors of Mondial.

ISBN 9781595691101

156 pages

Order in Europe: UEA (Rotterdam)

Order in North America: Mondial (New York City)

ABOUT THE BOOK: The first crime novel in the history of the original Esperanto literature, first published in 1920, and now linguistically slightly edited for our 2008 edition of Mondial. A fascinating story of murder and love affair…

Here is a rough English translation of the beginning of the first chapter of the novel:

"Robbery-murder, no trace, immediately send a capable official - mayor."

As a result of this telegram, directed to the main police station in Berlin, detective-commissioner von Merten with detective-policeman Kruse was sent to the small town of Altburg, from which the telegram came. They immediately set off and arrived in Altburg a little after three o'clock in the afternoon. There they went to the mayor, who in such small places is also the chief of the police.

"We find ourselves in front of a mysterious issue", said the mayor, accepting the two officials. He was a kind old gentleman, but the murder thing had obviously confused him completely. "The corpse of a young, beautiful lady was found in a bag; of the criminal there is, as I have already telegraphed, no trace at all, not even the smallest. You will have a very difficult task, gentlemen!”

"Where was the body found?" von Merten asked.

“In a forest, about an hour from here. The district judge returned from there not long ago, and he also telegraphed the prosecutor's office. But the prosecutor will probably not come until tomorrow, otherwise he would already be here.”

"When was the body found?"

"This morning around seven."

"Who found it?"

"Forest Jansen, or rather his dog, who led him to the place of discovery."

"Was the corpse still fresh?"

“Completely fresh. Doctor Osten believes that the crime can only have been committed last night. Such a beautiful young lady! Really, it's a shame!”

"Can you get us a vehicle as soon as possible so we can drive to the place of discovery? Is the corpse still lying there?”

“Surely it's still there. I stationed a policeman there, and the gendarme is probably still there too. Shall I call dispatcher Solm for a vehicle?”

"Please."

The mayor went to the phone and very soon returned, announcing that the vehicle would arrive in a quarter of an hour.

"So you will accompany us, Mr. Mayor?"

"If necessary, yes."

"It is not absolutely necessary, but it would be desirable, because presumably I will have to ask for information on some points."

"Well, fine, I'll come along."

The vehicle arrived, and they drove through the rough streets of the small town, then along a highway that first led through fields and meadows, then through a forest. Then they turned aside into a forest path. Finally, when they had driven down this road for about a quarter of an hour, they left the vehicle and went down a footpath. In a thicket lay the bag containing the corpse, guarded by the policeman. The gendarme had gone home to write his report and then come back.

Merten carefully pulled the bag away from the completely naked corpse, which he then closely examined.

"Well, do you see anything remarkable on it?" asked the mayor, to whom the matter seemed to be taking too long.

"The murderer belonged to a fhigher class of society, was a widow, had a good life, recently stayed or at least a short time ago was in Southern Europe, apparently she is English and very busy with writer's work."

"Can you see all that from the corpse?"

“Even very clearly. See the well-groomed hands and feet. Well-kept hands are very common, but careful care of the toenails is a thing only in the higher circles of society, i.a. because it always has to be done by another person. And lo and behold!” He picked up a delicate, black fiber that was stuck between the second and third toe of the left foot, barely noticeable.

"What is that?"

"A piece of thread," said the mayor, after he had looked at it carefully.

“Quite right. And from what fabric?”

"I don't know that."

"From silk." Merten pulled a magnifying glass from his pocket and handed it to the mayor. “So, she was wearing silk stockings, another sign of her class. And now look at the foot as a whole, what does it show?”

"Nothing to me, I must openly confess."

“With the exception of the sole, it does not have even a little hardening of the skin anywhere. So the lady always wore precisely fitted shoes. Accordingly, she did not buy her shoes in a warehouse, but had them made to measure. That is much more expensive, so it speaks for itself that she had a good income, as well as the silk stockings."

“That is correct. But more: why is she English?”

"I still don't say that for sure, but it's probable. Look again at the foot, feet are very instructive. The sole is flat. That could not have been if she, like most ladies, had worn shoes with high heels to make her feet appear smaller. Getting used to high-heeled shoes causes the feet to bend in such a way that the front part goes down more...

Sten Johansson: "Sesdek ok" ("Sixty-eight")

This is a novel (2021) written originally in Esperanto (i.e. not translated from any other language) by the Swedish Esperanto author Sten Johansson. Born in 1950 and one of the best-known modern writers of fiction in Esperanto, Johansson has written more than 25 books in the international language Esperanto, mostly novels and short stories. He also translates into Esperanto and writes in Swedish, his native language. This interesting novel, "Sesdek ok" is the eighth books by Sten Johansson published by our company, Mondial.

ISBN 9781595694126

186 pages

Order in Europe: UEA (Rotterdam)

Order in North America: Mondial (New York City)

ABOUT THE BOOK: The year 1968 was an eventful year, in many parts of the world: in the United States, the protests against the US government's war in Vietnam intensified, and in Czechoslovakia the so-called Prague Spring first blossomed and then, in the same year, was crushed by the armies of the Warsaw Pact. The novel mentions both events, but focuses on a third tumultuous event: the student uprisings in Paris.

Through the eyes of a young Swedish Esperantist studying French literature in Paris, the author presents the social situation of France at that time and intertwines his descriptions with issues of interpersonal relationships, love and affection, which he skillfully uses as illustrations of various political movements and individual convictions.

Here is a rough English translation of the end of the sixth chapter of the novel:

One morning, I went into the girls' bed, though they were both still lying in it, for Marie-France would not work that day. I managed to get in the middle, between them, and although Marie-France did protest, she stayed at least for a while. I stroked Dani, and at the same time tried to tickle Marie-France, but she reciprocated with knees and elbows, saying there was no room for a trio in bed. In fact, she was right, and that reminded me of Chris' mentioning at some point that Dani wouldn't be able to accommodate me. At that time, I found the fact — that she was sharing a bed with another girl — a bit disturbing, but now I got used to it and was no longer too shocked. Marie-France seemed like my and Dani's sister, while Dani and I were almost lovers and certainly not siblings. A bizarre family, no doubt — that’s how I felt.

After a while, Marie-France got up and started making coffee for all of us. While doing this, she felt the urge to chat about her boyfriend. She said that, among the students, there have been for quite some time various radical groups challenging social conditions, teaching processes at the university, and, perhaps most of all, the American warfare in Vietnam. I didn’t quite understand how the university was to blame for the latter, but I did agree that it was a heinous crime...

Marie-France further explained that, in recent years, the number of students at French universities had grown enormously, although almost all of the students still come from bourgeois or at least petty-bourgeois families. The universities, however, have not changed at all; the teaching, the methods, the sites remained extremely old-fashioned and insufficient for the growing student body.

Earlier in January, there was a clash between students in Nanterre and the police during a demonstration. Now, during another demonstration for Vietnam on March 20, the police arrested a number of students, and for this reason, two days later, a group of students, in which Marie-France's boyfriend Henri took part, occupied in protest a hall of the university. Because this happened on March 22, they were named the "March 22 movement". In connection with this, Marie-France mentioned, for the first time, the name of Daniel Cohn-Bendit. According to her, Henri greatly appreciated him and called him a talented leader and agitator.

To me it was a surprise how much the former colonial wars of France still mean today. I thought I knew that most French colonies south of the Sahara had already become independent without fight, and there probably hadn't been any wars there either, as before in the former Belgian Congo or now in ex-British Nigeria. But the current U.S. war in Vietnam was indeed simply a continuation of the French colonial war in Indochina, and even more recent than that was the war in Algeria, which continued to seem a cause of political conflict, accusations, and perhaps even attacks, within France.

At the Sorbonne, I have not yet noticed student protests or actions. The teaching in my course continued according to the same routine as before; the lectures were equally discouraging, and we foreign students had to deal with understanding the practical use of the French language. And I did. Although in Belleville, where we lived, the French language was not exactly the same as at the Sorbonne. Here in Belleville,I had scarcely an opportunity to practice the imperfect subjunctive, and of course the passé simple was simply a past tense. And I’m not entirely sure whether the ways of ellipsing or shortening sentences follow exactly the same pattern in the two places.

In the literary field, at the Sorbonne, we have already advanced through the 18th century — on the road from Voltaire and Rousseau to Prévost and his "Manon Lescaut" — and the reading list for the next period consisted exclusively of Hugo and Balzac. I was very doubtful whether we would ever reach the writers preferred by Dani.

In early April, I was shocked by the news of the assassination of Martin Luther King, the leader of a peaceful movement for civil rights of all Americans. One more historical hint that the world is not really progressing. I wondered in what direction the United States was going. The war in Vietnam continued and seemed more and more brutal. Some time ago, I saw a photo of the police chief of Saigon, who triumphantly shot a prisoner in front of the cameras. Obviously, that victim was just one of thousands killed. During a short visit, Henri talked about it:

"Massacres occur every day, and the US bombardment with napalm and defoliating poisons affects the entire population, regardless of their sympathies or antipathies."

On the other hand, the radio reported another piece of news, more gratifying. Czechoslovakia has just elected a new leader who has promised democratic reforms and ‘socialism with a human face’. Obviously that couldn’t make up for the war in Vietnam, maybe not even for a few murders. However, it seemed to me a tiny bright light in the dark.

Trevor Steele: "Sed nur fragmento" ("But just a fragment")

This novel is a modern classic from 1987, written originally in Esperanto (i.e. not translated from any other language), by the Australian Esperanto author Trevor Steele. Steele was born in 1940, and his list of books in Esperanto is just as long as Sten Johansson's - more than 20! The first and second editions of this title were published by the Brazilian Esperanto publisher Fonto. This third edition from 2020 was published by Mondial.

ISBN 9781595694072

429 pages

Order in Europe: UEA (Rotterdam)

Order in North America: Mondial (New York City)

ABOUT THE BOOK: The well-known Esperanto author Trevor Steele recreates, on the one hand, the society of the city of Brisbane (Queensland, Australia) in the 19th century and, on the other hand, the barely affected culture of the island of New Guinea ("Green Island" in the novel) — through the eyes of the Russian anthropologist Baron Maklin. The novel is colorful and eventful. Steele knows how to write so interestingly that in the beginning one almost forgets that it is a novel; one reads with complete interest as if it were a travelogue by a true anthropologist. During his years in this part of the world, Baron Maklin progressed, as a person, from naivety to political engagement, from being uninterested in the other sex to being in love, from scientism to mysticism, from a person of cold objectivity to a defender of humanity... Reviewers rated it one of the best original novels ever published in Esperanto.

The late US-American book reviewer Don Harlow, an esperantist himself, wrote the following review:

Between the time of Copernicus and that of Einstein, the universe was distinctly mechanical; it was assumed that, provided one had all the relevant data, one could predict the whole future, the development of everything. After Einstein, however, quantum physicists showed up, i.e. Planck and Heisenberg and Schrödinger and Hawking, who destroyed this mechanic approach by the "Principle of Uncertainty". And today, the theory of Chaos largely prevails. In a true sense, our understanding of the universe returns to its roots: mysticism.

This novel reflects the same evolution, but through the life of a single man: Baron Nikolai Ivanovich Maklin. On the pages of the novel, covering only a few years, Maklin progressed, as a person, from naivety to political engagement, from being uninterested in the other sex to being in love, from scientism to mysticism, from a person of cold objectivity to a defender of humanity, and from insignificance to the final fulfillment: death.

As a young student, confused by the political fears of the tsarist government in St. Petersburg and strongly influenced by a single scientific work, "The Enigmatic Universe", Maklin migrated to Heidelberg, Germany, where he found himself in the group of disciples around the strong-willed and mechanistic scientist Kehl. Later, dedicating his life to adding items to the "magnificent mosaic" of Kehl's science, the anthropologist Maklin traveled to the "Green Island" (New Guinea) to study its inhabitants and their culture, only later realizing that the Russian government, in the person of his patron Archduke Dmitry, wanted to use him as a Trojan horse to annex the island.

The novel begins with his arrival on "Green Island"; it follows him through a year on the island, and later to Australia, where he takes up the post of head of a science station near Brisbane in Queensland, and finally back again to the Green Island, where he must find some way to protect the people and their land from annexation — a people he had previously learned to love and — he supposes — to understand. Maklin also learns, not about women, but about his own reactions to them — in the person of the beautiful Green Islander Ponigala, but more importantly through falling in love with Belinda Horne, the girlfriend of one of his dearest friends, the young English teacher and Kehl disciple Tom Layton. His relations with the Green Islanders and his subsequent discovery of the situation of the Australian Indigenous people, lead him from the impartial objectivity of a scientist to the empathic reaction of a human being. And most importantly, his scientific and philosophical attitude towards the universe is influenced by various events completely different from Kehl's worldview...

The novel is much more colorful and eventful than I can sketch here. I consider it one of the best novels to date published in Esperanto. It is extraordinary in size and technically pleasing in presentation, but also original in the choice of subject matter... An incredibly rich source.

Kalle Kniivilä: "Idoj de la imperio. La rusoj en Baltio" ("Children of the Empire. The Russians in the Baltic States")

Current topic; originally in Esperanto; non-fiction.

For his third book, Kalle Kniivilä traveled through the Baltics and spoke with Russian-speaking inhabitants who remember World War II and with others who were born after the fall of the Soviet Union.

ISBN 9781595693198

186 pages

Order in Europe: UEA (Rotterdam)

Order in North America: Mondial (New York City)

ABOUT THE BOOK: What exactly do the native Russian-speakers in the Baltic countries miss when they miss "home"? One million Russian-speakers live in Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania — one of the largest minorities in the European Union.

When the Baltic countries became independent, many of the Russians were left without any citizenship. They are not seldom treated as foreigners in the country where they were born or lived most of their lives — in the Baltic countries. But are Russian-speakers really Putin's "fifth column", are they ready to betray their compatriots in the Baltic countries, if Russia calls?

In his third book, Kalle Kniivilä traveled through the three Baltic countries and spoke with Russian-speaking inhabitants who remember World War II, and with others who were born after the fall of the Soviet Union.

He met a Russian-speaking bar owner whose waiters are not allowed to speak Russian — and Esperanto musicians who played for bandits in the wild 1990s.

About " Children of the Empire": Kniivilä's interviewing style is economical and electrifying. He portrays people with a wide variety of thoughts and opinions, not judging or demonizing. The result is a sharp analysis that explains the consequences of contemporary Russian politics.

Maria Georgieva, Svenska Dagbladet

Kalle Kniivilä is a journalist at Sydsvenska Dagbladet in Lund, Sweden. His previous books in Esperanto are Homoj de Putin (Putin's People; 2014, second edition 2016) and Krimeo estas nia (Crimea is Ours; 2015).

George Orwell: "Mil naŭcent okdek kvar" ("Nineteen Eighty-Four"; "1984")

The novel Nineteen Eighty-Four by the British author George Orwell (1903-1950) appeared in 1949 and depicts a society that is both utopian and real, as the translator, Donald Broadribb, emphasizes in his Preface: Utopian, because in the 1940s, the world of 1984 seemed distant and unimaginable; and real, because we know today, from history, that there have been and still are forces that strive for socially similarly radically oppressive and all-observant social orders as presented in the book.

ISBN 9781595692498

186 pages

Order in Europe: UEA (Rotterdam)

Order from the publisher: Mondial (New York City)

Other online bookstores: bookdepository; eurobuch; buecher.de; ozon.ru

ABOUT THE BOOK: In Nineteen Eighty-Four, the world is divided between three superstates that are constantly at war with each other. The novel describes life in one of them, Oceania, mainly in Airfield One (UK) and its main city, London. It tells the life of Winston Smith, who pretends to be a faithful member of the ruling Party, and his path to rebellion and a secret affair, as well as its consequences.

Several words or phrases invented by Orwell for this classic novel have entered into the English language, such as Big Brother is watching you, doublethink, thoughtcrime or Newspeak. The name of the author himself resulted in the adjective Orwellian, which refers to the manipulation of the thought of the masses by authorities, or to an organized secret observation of people's lives.

But, quite ironically, this "Novparolo" (Esperanto word for Newspeak), whose aim – in the novel – is to limit people's vocabulary and thus prevent them from thinking in an overly complex way, has several features in common with the language Esperanto itself, into which the novel is now translated. This common trait is not entirely accidental, as the wife of the famous Esperanto speaker Eugene Lanti, Ellen Kate Limouzin (Nelly), was also George Orwell's aunt; it is supposed that through her, Orwell had at least some knowledge of the structure of the international language Esperanto.

PS: This websites is published by the Esperanto publishing house Mondial (located in New York City), whose books are printed on three continents (North America, Europe, Australia) and distributed worldwide. If you are looking for Esperanto books published by other publishers, please check the bottom of this page.

Mondial publishes books in and about Esperanto, works originally written in Esperanto and books translated from many languages into Esperanto. It publishes fiction and non-fiction: prose, poetry, dictionaries, and specialized books dealing with various topics.